Suggested reading: Part One: Motor City.

The next scheduled stop on my trip was Syracuse in upstate New York. I wasn’t meeting my friend there for a few days so I had some time to make my way across leisurely.

Planning my trip East from Detroit I had the lyrics of Detroit or Buffalo looping around in my head:

Better pack up and go

Detroit or Buffalo

Anybody wanna know where, I don’t know

I don’t know

God knows everybody gotta go sometime

And I’m takin’ this train to the end of the line

Missin’ every mile that friend of mine

I wanted to take that train, if not to the end of the line than at least as far as Buffalo. I just didn’t feel like I’d be doing Barbara Keith justice boarding a Greyhound. That, I live in a (passenger) train-free area, and I don’t particularly enjoying short haul flying. So I wanted to use this trip as a chance to catch as many intercity trains as possible.

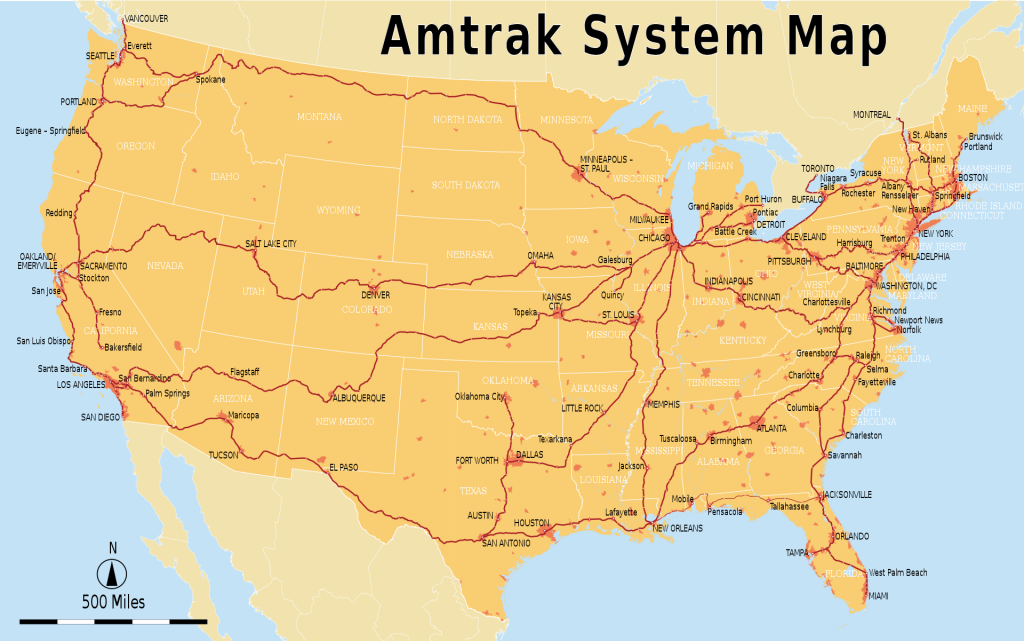

Unfortunately, heading East from Michigan is a huge blackhole in Amtrak’s often patchy coverage. It’s not as bad as Wyoming or South Dakota, but it’s pretty bad.

I guess Ohio never forked out for some State-subsidised local Amtrak service like the Cascades in Washington and Oregon or the Wolverine in Michigan. This means that only long distance trains pass through Ohio and they are set up for travel across the State more than within in.

The busiest of these is the Lakeshore Limited. She is a flagship long distance passenger train, connecting what might just be America’s two most traditionally transit friendly cities, Chicago and New York (also Boston, the train splits at Albany with half heading South to NYC and the other half continuing East). Sadly, like most long distance Amtrak trains the Lakeshore only runs once a day. It also leaves Chicago at 9:30pm which I believe is designed to provide a direct connection with the Empire Builder and California Zephyr coming from the West. They arrive in Chicago midafternoon, so I guess Amtrak wants some leeway so it’s not refunding tickets and providing complimentary hotel beds left, right and centre.

This all means that the Lakeshore hits Toledo, Ohio at the travel-friendly time of 3:15am. It’s hard to justify taking a five and a half hour train trip when you know you’ll sleep or be totally zonked out the whole way and arrive at your destination not yet able to check-in but too tired to enjoy the sights and sounds.

That’s annoying, but still manageable. What makes this train basically uncatchable is that the Amtrak Thruway coach that connects from Detroit to Toledo inexplicably leaves Detroit at 9:30pm, arriving in Toledo at 10:35, a casual four and a half hours before the Lakeshore Limited is due. I have no idea why this is the case, and since the Amtrak station in Toledo is in a quiet, mostly industrial neighbourhood at the edge of downtown, that would be a long wait. Oh, and the Lakeshore runs late around half the time, earning it the clever nickname the “Lateshore Limited’.

So, I gritted my teeth, hit pause on Detroit or Buffalo and pressed play on Simon and Garfunkel’s America.

If I wasn’t so tight (and stubborn), for around 250 USDs there are multiple daily direct flights between the two cities. But I am (on both counts) and so I paid $70 for the pleasure of taking a series of crowded coaches to make the trip.

At 4:30pm, half an hour late, I boarded the bus from Detroit’s unloved Greyhound station bound for Cleveland. There I had an hour to attempt to find something to eat in the area that didn’t come from a vending machine, before jumping on a full Baron’s bus bound for Buffalo that pulled in at 11:30pm.

It was a long evening.

In Buffalo

Having spent plenty of time in Detroit but barely visited anywhere else in the Rustbelt I was labouring under the false impression that the faded glory of turn of the century America was best experienced in Detroit. How wrong I was. Buffalo’s downtown architecture was at least as epic, and they had the inspired idea to stick a light rail through the Downtown spine a good 40 years before the Q-Line was conceived.

Downtown Buffalo rejuvenation

I was only in Buffalo for a hot minute and was mainly there as a stopping off point for Niagara Falls. In the wanderings I did manage on my brief visit I was struck by two things:

1. Vibrant queer scene!

Buffalo has a bustling theatre scene and what appeared to be a very prominent queer scene as well. I think the fact that I rolled into town on the last night of Pride was probably a factor here but the bricks and mortar presence of gay spaces make it apparent this wasn’t just a one-off thing.

I mean come on people Buffalo’s nickname is the Queen City.

2. Attempts to ‘bring back Downtown’

So prior to this trip my thinking about urban blight and declining downtowns in the Rustbelt and beyond went something like this:

- Early 20th century: Streetcar suburbs, manufacturing boom, prosperous bustling downtown.

- Mid century: Rise of the automobile, racial desegregation, growth of suburbia, freeway sprawl, loss of manufacturing jobs, decline of Downtown, abandoned buildings cleared for parking lots.

- Late 20th century: People realised suburbia is boring and diversity is good. Gentrification. Rise of Downtown as a cultural hub and desirable residential area with less of an emphasis as a commercial hub and very limited manufacturing (mainly just breweries).

In Buffalo I found out I was kinda right but I was missing a bit in the middle. What happened there (and I’m going to extrapolate and assume this was a general trend) was that when the decline began in the 1960s the city government put their heads together to figure out what they could do about it. This bit had always eluded me. I’d thought that once the Downtown starting to decline everyone just sort of shrugged and starting spending their time and money at suburban office parks and the new enclosed malls that sprung up on the edge of cities in the 1970s.

Being in Downtown Buffalo I realised that this was crazy. The architecture alone is staggering. City Hall looks like this:

The amount of wealth and prestige Downtown must have been incredible. And of course, all those fancy bankers, industrials and city officials want a nice, bustling area next door to their office and steady demand for their various premises.

So Buffalo came up with an ambitious plan to fix Downtown. The idea was that since suburbia had sucked a lot of demand away, the existing area was too large and not what people wanted. Best to turn Downtown into the equivalent of a giant outdoor shopping mall. To do this all the activity would be funneled onto a single main street which would be partially enclosed and flanked by parking garages accessible directly from the freeway network. A new light rail would run up that main spine.

The bit I had never really considered is that all this ‘urban renewal’ was phenomenally expensive. It required a lot of expertise and money in an increasingly broke urban environment. The city had one shot to reinvent itself in the post-automobile world and the landscape we got is the legacy of that era in cities across the world, but most notably in the Rustbelt.

Downtown Buffalo today

Today Buffalo is a mix of incredible art-deco and late 19th century architecture, a rather loud and imposing light rail that doesn’t run frequently enough and a very, very visible homeless population.

Even the single street that the aforementioned 1970s renewal plan funneled all the retail into, Main Street, is too long for the amount of commercial demand. So while there are vibrant stretches of the street, particularly up in the Theatre district, there’s an awful lot of dead space around too and that’s just on the main street (Main Street). In more recent years cars have been reintroduced to some sections of the street in an attempt to bring back some life, even if it’s just people moving to and from their parked vehicles.

Like Detroit, I got the impression that Buffalonians love their city (more than the regular amount) and have continued their city’s legacy of punching about its weight culturally.

There’s no doubt Buffalo has a lot of problems, but all in all it’s the sort of city I’m kinda sad we don’t have in Australia. A place with a rich and vibrant arts and culture scene that isn’t an ‘alpha’ city with x millions of residents and sky-high rents. A place you can afford to live in a walkable neighbourhood that has interesting things going on.

Is that too much to ask?

Next up: Part 3: Niagara Falls, USA

One last thing before you go:

I’ve more or less abandoned my facebook and twitter accounts so come find me on mastodon if you fancy that early 2010s twitter vibe. Alternatively, sign up to get emailed when I post.